If you’re like me, you’ve dreamed of the paperles office – the day when there will be no desk clutter, the copy machine will never be busy, and your copy of Macworld will come via electronic mail. But until recently, distributing documents electronically was nothing short of a nightmare. Unless senders were willing to confine themselves to ASCII text, they had to make sure that all the people reading the document had the same type of computer, the same programs, the same fonts, the same printer drivers, and so on. Publishing even a simple brochure electronically can make skywriting seem simple.

Adobe Acrobat 2.0 seeks to change all that. It allows you to create a file complete with fonts, formatting, graphics, and more. Using a special program, Windows, DOS, UNIX, and Mac users can read, print, and search the document, with the formatting intact. Acrobat 2.0 eliminates a number of Version 1.0’s shortcomings, and puts it in a position to revolutionize electronic publishing.

Adobe Acrobat consists of three main components. PDF Writer is a program that lets you create Acrobat documents to distribute. Acrobat Reader is a Freeware program that you can give other individuals to view your Acrobat files with. The Acrobat Exchange program allows you to add hypertext links and other features to your existing Acrobat files.

Acrobat’s PDF Writer

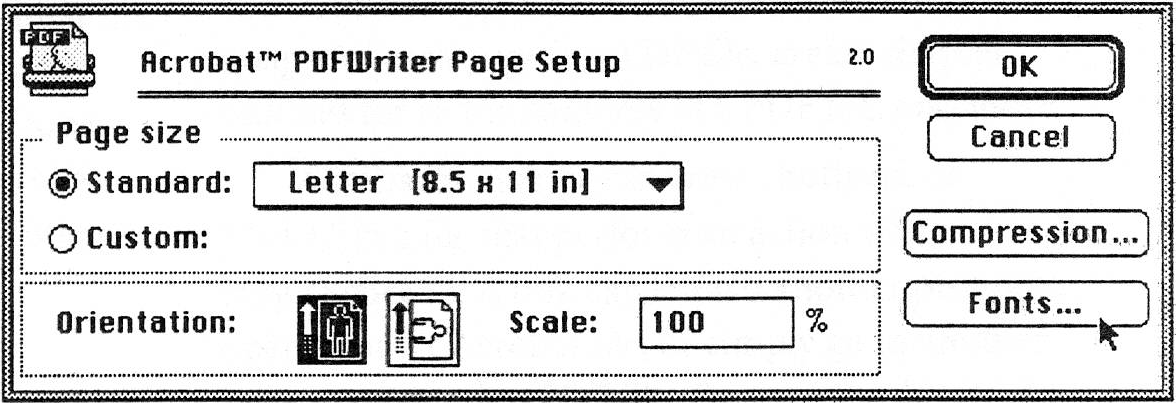

First, we’ll take a look at PDF Writer. Using it is simple – you design your document in any graphics program, DTP package, or word processor, then choose PDF Writer in the Chooser and print. Rather than sending the document to your printer, however, PDF Writer creates a Portable Document Format (PDF) file. Any user running the Acrobat Reader 2.0 can then view the file. Since most users don’t have full-page monitors, PDF Writer offers an easy way to set up your page to match the size of a standard 640 x 480 monitor. That way, an entire page of your document will fit on one screen, and users won’t have to scroll around as much.

I was pleasantly surprised by the size of most PDF files. A TeachText file with a few PICT images was only 100k in PDF format – just a tad more than the original TeachText file. When you begin to add more high-resolution images, though, file size can balloon. To save disk space, you can have Acrobat compress graphics in the PDF file. Several levels of JPEG compression are available, as well as a “lossless” compression. The compression yielded impressive results —with medium quality JPEG compression, I cut the size of a 16-page, graphics laden PDF file from 4.5 megs to just 1.5.

PDF Writer seemed to have trouble with some EPS files. Transparent areas of the images became opaque, lousing up complex layouts. I used Photoshop to convert the EPS files into low-res bitmaps, and the problems went away. If you want PostScript graphics in your PDF files, you might look into getting Acrobat Distiller, part of the Acrobat Pro package, that handles EPS graphics and other PostScript files perfectly.

Acrobat Reader

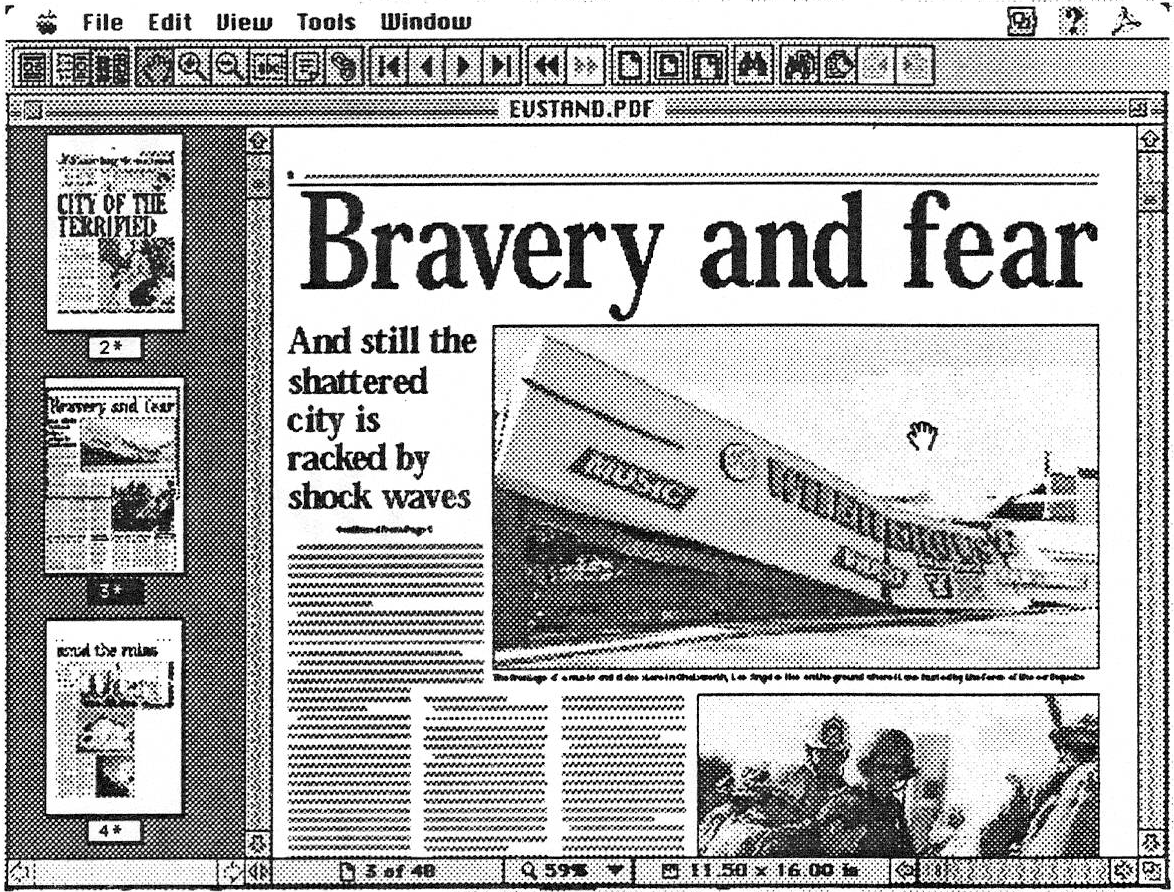

Once you’ve made the PDF file, you can distribute it to users. Acrobat Reader allows the user to view the PDF file on their screen, or print high-resolution hard copy. Onscreen, they can flip from page to page, zoom in and out, search for text in the document, and copy out text for use in other documents. If you’re security-conscious, you can password protect the Acrobat file to keep other users from copying out text or graphics, or from printing the document.

If a user doesn’t have one of the fonts used in the PDF file, Acrobat Reader creates a new font on the fly to match the characteristics of the missing typeface. Although the substitute fonts aren’t perfect matches, they do a great job of preserving spacing, line breaks, and the overall “color” of a page. Serif and Sans Serif fonts can be substituted, but script, display, and Dingbat fonts are left out in the cold. Fortunately, you can tell PDF Writer to include any TrueType or Type 1 PostScript fonts in the file. This balloons the PDF file’s size, but it means that the actual font you’re using is embedded in the PDF document —no need for substitution.

In version 1.0, Adobe made the mistake of charging for Acrobat Reader. Acrobat files weren’t widely distributed, since few people had the reader. But no one bothered getting the reader, as Acrobat files were almost non-existent. See the loop here? Fortunately, Adobe is atoning for this sin with the new version. Acrobat Reader 2.0 is available on online services, Planet BMUG, the Internet, and many BBS’s. Acrobat Exchange even comes with two copies of Reader – one for Mac, and one for Windows. You can use Apple’s DiskCopy program to duplicate the Windows disk if you don’t want to give away your only copy.

Acrobat Exchange

Up to this point, I’ve only described using PDF Writer and Acrobat Reader. Those programs are exciting in themselves, but Acrobat Exchange, the third part of the commercial Acrobat package, is fantastic. It allows you to enhance a regular old PDF file with hypertext links, generate thumbnail images of each page in a PDF file, create chapter outlines for all the contents of a PDF file, and more.

Acrobat Exchange can create buttons, or “links,” in a file that perform an action when they’re clicked. A link can launch another program, open another Acrobat file, or simply go to another page in the current PDF file. One use for this might be an interactive table of contents for a digital magazine. When you click on an entry in the table of contents, you’re taken right to the article it describes. Clicking on a technical term in a research paper could take you to a glossary of terms. The possibilities are almost endless.

Thumbnail images of each page can be created in Exchange, and users can navigate through the document by clicking on the thumbnails. You can also create “bookmarks” that appear in the margins, and take you to specific pages when clicked. It’s easy to use these bookmarks to create a table of contents. It’s even possible to imbed notes in a PDF file that behave like digital Post-It™ notes. A small paper icon appears tacked to the page, and double-clicking on it reveals the note.

One pet peeve of reading documents onscreen is the amount of mousing around that’s needed. On my 13-inch screen, a multi-column article forces me to read to the bottom of the page, go back up to the top, read to the bottom again, and so on. If articles are continued on another page, even more scrolling around is needed. Acrobat solves this problem by allowing you to define particular articles as being separate from other text. By linking different columns together, even on different pages, you can allow a user to navigate through an article without touching the scroll bars. They just click on the particular article, and Acrobat scrolls to the next section automatically.

Acrobat Sampler CD

One gem that’s easy to overlook is the included Acrobat Sampler CD. This CD-ROM contains hundreds of sample PDF files, including the complete works of Shakespeare, Aesop’s fables, excerpts from Wired magazine, the Constitution of the United States, a collection of cowboy poems, a guide to computer jargon, a great cookbook, a guide to London hotels, and much more. There’s something for everyone on the disk—I enjoyed just browsing through it with Acrobat, and the files in it are great demonstrations of the program’s hypertext capabilities. If you’re using Acrobat and need some inspiration, check out the CD.

My only gripe about Acrobat is the speed – displaying pages can be very slow, even on my Centris 650, and creating a large, image-filled PDF file took almost 20 minutes. Fortunately, the program allows you to interrupt screen redraw if you realize you want to go to a different page. It’s also possible to “greek out” large pictures to speed up redraw, although many attractive layouts can be marred when the graphics are replaced by flat gray shapes.

Despite the speed problems, I can easily recommend Acrobat for individuals who want to jump on the electronic publishing bandwagon, or need a way to distribute documents without using reams of paper. Well thought-out features, like hypertext links, and the ability to isolate individual articles, make Acrobat Exchange an extremely powerful tool. Using the program is easy, and I only had to consult the excellent manual a few times. You can easily start pumping out PDF files with PDF Writer and distributing them unmodified, but Exchange’s additional capabilities allows you to add new possibilities to any magazine, brochure, or document.

Other Electronic Publishing Solutions

- ASCII Text: OK, this is the option no one likes to talk about. For all its lack of pizazz, distributing documents in plain text format can be useful. Anyone in the known universe can read ASCIl text, there are no problems preserving formatting, and plain text consumes little disk space.

- Setext: Setext format (short for Structure Enhanced Text) is a special offshoot of plain ASCIl text. By inserting certain characters in your document at key places, you can mark section and chapter divisions in your text. Although anyone can read setext (it’s still just ASCIl), the Freeware program Easy View allows you to see the chapter divisions and other special formatting. A Windows setext viewer is also available.

- DocMaker: This venerable Shareware program lets you combine text, pictures, sounds, and even QuickTime movies. Since files are saved as self-running programs, font compatibility is the only concern. However, DocMaker’s page layout capabilities leave something to be desired – multiple columns are impossible.

- Common Ground: Like Acrobat, this commercial program allows you to create a digital duplicate of any document you can print from your Mac. It offers Mac and Windows viewers that require little disk space, and it’s less expensive than Acrobat. However, Common Ground’s image quality is lower, and it lacks the hypertext features that make Acrobat so attractive.

- QuickDraw GX: QuickDraw GX allows users to print transportable documents that can be viewed on any Mac. Any Mac running QuickDraw GX, that is. Due to incompatibilities and high memory requirements, few users are adopting the new Apple technology at present. In the future, however, GX may be the electronic publishing format of choice.