In the early '90s, every page was a handcrafted labor of love. Sadly, anyone who managed a large site eventually hit the wall: writing piles of custom HTML that tangled valuable content with boilerplate markup, gnarly design tweaks, and other difficult-to-maintain cruft.

Soon, large sites abandoned handcrafted pages entirely. The meat of a page got stored in a database, then passed through HTML templates to “wrap” it in design elements like footers, sidebars, and banner ads. Today, even individual elements like the name of a book, a photo of its cover, and an author’s bio are often teased out of design-heavy HTML and stored as individual chunks. Content editors fill out input forms rather than wrestling with a blank HTML canvas, and CMS templates reshuffle the elements as needed.

Trouble in Chunkytown

This fields-and-templates approach works great for content that follows predictable patterns, like product information sheets, photo galleries, and podcasts. It’s at the heart of NPR’s successful “Create Once, Publish Everywhere” system, and it’s hard to find a CMS or web publishing tool that doesn’t offer some way to model different types of content.

But Team Chunk has a deadly weakness. When narrative text is mixed with embedded media, complex call-outs, or other rich supporting material, structured templates have trouble keeping up.

MSNBC.com is a perfect example. As part of its 2013 redesign, the cable news channel put more emphasis on in-depth, web-first news coverage. The design included several reusable modules that could be placed on template-driven pages: videos with accompanying playlists, photo galleries, polling widgets, and teasers for related articles. That standardization delivered all the benefits of CMS content modeling: it made the design more consistent, simplified the process of reusing rich multimedia elements across different stories, and kept the responsive CSS rules manageable.

Unfortunately, reporters and editors insisted it would cripple their work. They needed to mix in multiple videos, a gallery and a poll, or several related article teasers, at specific points in each article. Carving out these elements into separate CMS fields or standalone pieces of content would make storing and remixing them easier. However, relying on rule-based CMS templates to display them would also break their connection to the specific sentences, paragraphs, and sections they were meant to enhance.

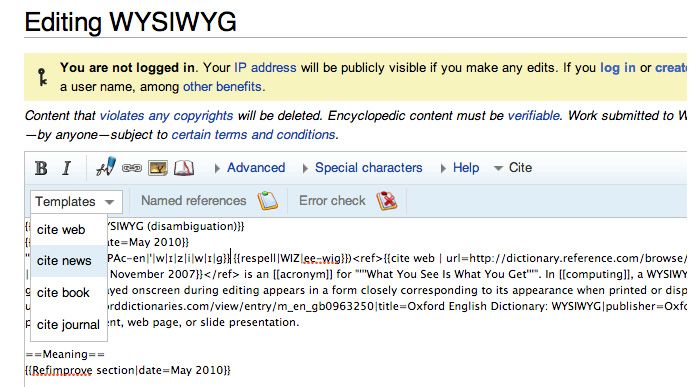

This is how complex markup makes its way into an article’s body field. Soon, WYSIWYG tools are added to help editors with limited HTML skills. Before anyone realizes what’s happened, use of presentation-oriented markup explodes. Mobile layouts break, and the already difficult task of cross-channel content reuse becomes even harder.

A blog post with embedded tweets, a comparison review that illustrates each product with a photo gallery, and a story that pulls in supporting material from a previous article all face the same problem: the fields-and-templates approach doesn’t work for these small pockets of structure.

Why “clean markup” won’t help

If you grew up during the WYSIWYG Wars—when tools like Adobe PageMill and Microsoft Word’s “Save to Web” feature splattered hideous markup across the internet—you might think cleaner HTML markup is the answer. Kill those unnecessary style attributes, ensure that <p> tags are used instead of <br />, use <ul> tags properly, name your CSS classes carefully, and things will fall into place!

Clean, semantic markup is important, but it won’t solve complex structural problems, like MSNBC’s need to embed widgets into narrative text. We have workhorse elements like ul, div, and span; precision tools like cite, table, and figure; and new HTML5 container elements like section, aside, and nav. But unless our content is really as simple as an unattributed block quote or a floated image, we still need layers of nested elements and CSS classes to capture what we really mean.

Imagine embedding a simple photo gallery in an article. Its markup might be clean and semantically correct, but the fact that the gallery displays with a headline, three photos, a link to a dedicated page, and a caption? Those are design decisions that may change in the future, and we need to separate them from the markup mapping our content to HTML.

<aside class="gallery">

<h1><a href="gallery1.html">Gallery Title!</a></h1>

<figure>

<a href="photo1.html"><img src="photo1.jpg" /></a>

<a href="photo2.html"><img src="photo2.jpg" /></a>

<a href="photo3.html"><img src="photo3.jpg" /></a>

<figcaption>Custom caption</figcaption>

</figure>

</aside>

The problem isn’t restricted to the publishing industry, either. My team recently encountered similar challenges building a health insurance portal for a company’s HR department. Most content on the 50,000-page site included complex step-by-step instructions, special steps for specific types of employees, or call-outs appropriate for workers in one country but not another. Even with a WYSIWYG editor, the HTML structures needed were far too complex for the site’s business users to create.

At its heart, the problem is a vocabulary mismatch. While standard HTML is rich enough for a designer to represent complex content, it isn’t precise enough to describe and store the content in a presentation-independent fashion. This is why WYSIWYG tools can make the problem worse: rather than shielding content creators from the complexity of markup, they make it easier to describe content using the wrong vocabulary.

Now, as we attempt to combine multi-device design requirements with complex, media-rich narratives, we’ve hit the wall. The chunky, fields-and-templates approach we’ve developed can’t save us from the mismatch between our content and HTML’s descriptive tools.

Meanwhile, in XML-world

While fields and templates have come to dominate web publishing tools, the XML world has spent nearly 15 years developing a parallel approach. Rather than chunking content into fields and re-assembling it later, the XML community embraces fluid, markup-based documents. To capture meaningful structure and avoid HTML’s browser-specific presentation pitfalls, they define purpose-specific collections of markup tags for different projects and applications. It’s a versatile approach that has crossed paths with the web publishing world: the XHTML standard is just HTML, defined as an XML schema.

The Darwin Information Typing Architecture standard—better known as DITA—is a mature example of this approach. Developed by IBM and announced in 2001, DITA was shaped by the technical documentation community. As far back as 2005, Adobe used it to store and manage Creative Suite software manuals—more than 100,000 pages thick with illustrations, cross-references, and complex metadata, all in 14 languages. Both the print and online editions were generated from the same pool of DITA files.

DITA’s heart is a family of standard XML schemas that define a rich vocabulary of content elements. HTML-compatible tags like <ol> and <p> are used for simple formatting, but the standard also defines hundreds of additional tags and properties to describe complex concepts. In addition, it includes provisions for “specializations”—add-on vocabularies for a given industry or project.

<task id="signup">

<title>Signing up for health insurance</title>

<taskbody>

<steps>

<step>List your dependents</step>

<step>Gather past medical information</step>

<step>Fill out forms 21a, 39b, and 92c</step>

<step audience="retail">

Hand in your paperwork to a supervisor

</step>

<step audience="corporate">

Deliver your paperwork to the HR office

</step>

</steps>

</taskbody>

</task>

<p conref="../boilerplate.xml#disclaimer">

This text will be replaced by the boilerplate legal disclaimer.

</p>

Once these semantically precise documents have been created, a transformation step is necessary to turn the structured content into final output. A web publishing tool might read a directory of DITA XML files, replace placeholder elements with the text they reference, expand custom tags into styled HTML markup, strip out text that’s only intended for printed manuals, and so on.

The approach isn’t without its downsides. Managing large collections of related articles and documents requires the users editing them to understand the nuances of the specific relationships, and how they’ll affect the final product. While the simplest DITA schema is similar to HTML, other variations add hundreds of special-purpose tags and properties.

In the broader web publishing world, it can take more customization to achieve the same benefits. Although the semantically rich content is cleaner and easier to repurpose, building usable editorial tools and publishing processes on top of DITA can be just as daunting as building a complex, multichannel website.

The best of both worlds

The good news is we don’t have to convert all our projects to XML to learn from those communities’ accumulated wisdom. While the toolchains that have been built around those approaches are a tough fit for today’s mature web development tools and workflows, we can use their principles in our projects.

Store meaning, not appearance, in the body

When complex markup structures appear in narrative text, boil them down to the basics. Replace complex house styles with custom tags that describe their precise meaning, like <warning type="hardware">Don't turn off the server!</warning>. When a new tag isn’t appropriate, use custom attributes. The DITA audience attribute is a good example. It can apply to many different kinds of elements, but jamming it into the often-abused CSS class attribute would muddy its meaning.

More complicated elements inside a body field, like multi-image galleries or metadata-heavy media embeds, should be broken out into separate content fields. If they’re meant to be reused across multiple pieces of content, make them freestanding content items in a CMS. Instead of relying on rule-based templates to position them, however, use placeholders like <gallery id="1" /> and <teaser article="82" rel="rebuttal" /> right inside the narrative fields.

This approach turns an article or a post into a kind of manifest, with narrative fields like “Body” and “Summary” playing traffic cop for the collection of properly separated supporting elements. Later, on output, they can be stitched back together.

Tailor editorial tools for the same meaningful elements

Editors and creators who work with complex content need tools that manipulate that content’s native vocabulary, not the final visual design or the browser-specific nuances of HTML. Wikipedia recently rolled out an assistive editing tool to help new users navigate the complexity of the site’s content. It offers a limited set of formatting tools, but gives editors one-click access to Wikipedia-specific markup standards like inline journal citations, boilerplate text, and calls for editorial review.

Those kinds of decisions aren’t universal: they’re tailored to the peculiarities of a specific project’s content. Disabling all but the most basic HTML tags and adding one-click buttons for a site’s custom elements can turn a “stock” WYSIWYG editor into a structure-friendly tool. It’s also the best way to avoid the click-buttons-till-it-looks-right markup mess.

Transform the content to match the designs

When the time comes to publish the content, we can transform these custom tags and placeholders to the final destination format. If the design changes, tweaks need only be made in the code or templates that transform the markup—not in every piece of content where the structures appear.

In addition, different transformations can be applied to those custom elements depending on the context. The <gallery> element mentioned earlier might be replaced by multiple captioned and credited images for most web browsers. On bandwidth-constrained mobile devices, a single thumbnail image and links to the full gallery could be inserted instead. Contextually appropriate decisions can be made for email summaries, partner content APIs, or RSS feeds; each is just an alternative transformation step.

That processing doesn’t even need to happen on the server side. Client-side tools like jQuery and AngularJS can be used to apply complex behaviors based on custom attributes, style and interact with custom elements, replace placeholders with standard markup, or lazy-load media that’s tailored to a device’s needs.

The best news: it’s possible today

This triad of techniques—using custom elements and properties to represent content’s meaning, transforming it into HTML on output, and ensuring editing tools share the same vocabulary—has already started to gain momentum in the web publishing world.

WordPress’s “Short Tags” are a simple application of the technique, and third-party plugins can present editors with a customized set of placeholder tags tailored to their needs. Although WordPress’s use of bracketed placeholders like

EZPublish, a popular PHP-based CMS, allows content to be stored as XML rather than HTML. Developers can set up custom tags whose properties and content are mapped to templates for output. Although it’s not automatic, these custom tags can be integrated into EZPublish’s native editing tools, so content creators don’t have to use raw markup to enter them.

<custom name="about_author" photo="author.jpg" user_account="77" >

The author wrote this article over a long holiday break, and regrets any eggnog-induced errors.

</custom>

Drupal 8, currently under development, will ship with the CKEditor WYSIWYG tool. It will come pre-configured for a minimal set of HTML tags, but will use HTML5 data attributes to store additional properties like captions, layout hints, and more on simple elements. When the content is rendered, Drupal’s text filters will transform it into the final representation: CSS classes, <figcaption> tags, and so on. Users can manage that complex information using CKEditor’s visual tools instead of raw markup, but storing precision content while outputting semantic HTML will be the default.

A bright future

This approach to structured content won’t always rely on complex web publishing tools. Several related HTML5 standards, grouped under the Web Components umbrella, will eventually make it possible to perform these transformations in the browser itself. The ability to define custom elements will bring us closer to XML’s vocabulary flexibility, browser-supported HTML templates will be able to replace those elements with more complex representational markup on the fly, and the Shadow DOM will give designers a way to “sandbox” complex Javascript and CSS interactions inside those custom elements.

Browser support for these behaviors is understandably patchy, but tools like Polymer are designed to fill the gaps. In the meantime we can still depend on existing HTML elements, enhanced with data attributes, to stand in for custom ones. Although we still have to do the work of transforming them, they bridge the gap between a precise, tailored content vocabulary and clean, browser-friendly markup.

What are the next steps?

Using this narrative-friendly approach to structured content isn’t a cakewalk. Site builders, content strategists, and designers must understand what’s happening inside the body field, not just the database-powered chunks that surround it. Which patterns in our content should rely on simple styling, and which merit their own custom tags? Which can we assume will stay consistent, and which should account for future changes? Our planning process must start answering those questions.

In addition, content editing tools must be tailored to reflect those decisions. Too many users are accustomed to presentation-oriented “Dreamweaver in a body field” WYSIWYG tools, and throwing them back into the land of raw markup is a recipe for disaster. Although the current crop of web WYSIWYG tools can all be customized, actually tweaking them to match the vocabulary of a site’s content rarely happens when deadlines loom.

But the payoff can be dramatic. Richer, more flexible designs can coexist with the demands of multichannel publishing; future design changes can sidestep the laborious process of scrubbing old content blobs; and simpler, streamlined tools can help editors and authors produce better content faster. By combining the best of XML and structured web content, we can make the body field safe for future generations.