If you build or manage public-facing websites, you’ve almost certainly heard the excited buzz around personalization technology. Content marketers, enthusiastic CEOs, and product vendors all seem to agree that customizing articles, product pitches, and support materials to each visitor’s interests — and delivering them at just the right time — is the new key to success.

Content personalization for the web isn’t new, and the latest wave of excitement isn’t all hype; unfortunately, the reality on the ground rarely lives up to the promise of a well-produced sales demo. Building a realistic personalization strategy for your website, publishing platform, or digital project requires chewing on several foundational questions long before any high-end products or algorithms enter the picture.

The good news is that those core issues are more straightforward than you might think. In working with large and small clients on content tailoring and personalization projects, we’ve found that focusing on four key issues can make a huge difference.

1. Signals: Information You Have Right Now

A lot of conversations about personalization focus on interesting and novel things that we can discover about a website visitor: where they’re currently located, whether they’re a frequent visitor or a first-timer, whether they’re on a mobile device, and so on. Before you can reliably personalize content for a given user, you must be able to identify them using the signals you have at your disposal. For example, building a custom version of your website that’s displayed if someone is inside your brick-and-mortar store sounds great, but it’s useless if you can’t reliably determine whether they’re inside your store or just in the same neighborhood.

Context

The simplest and most common kinds of signals are contextual information about a user’s current interaction with your content. Their current web browser, the topic of the article they’re reading, whether they’re using a mobile device, their time zone, the current date, and so on are easy to determine in any publishing system worth its salt. These small bits of information are rarely enough to drive complex content targeting, but they can still be used effectively. Bestbuy.com, for example, uses visitor location data to enhance their navigation menu with information about their closest store, even if you’ve never visited before.

Identity

Moving beyond transient contextual cues requires knowing (and remembering) who the current visitor is. Tracking identity doesn’t necessarily mean storing personal information about them: it can be as simple as storing a cookie on their browser to keep track of their last visit. At the other end of the spectrum, sites that want to encourage long-term return visits, or require payment information for products or services, usually allow users to create an account with a profile. That account becomes their identity, and tracking (or simply asking for) their preferences is a rich source of personalization signals. Employee intranets or campus networks that use single-sign on services for authentication have already solved the underlying “identity” problem — and usually have a large pool of user information accessible to personalization tools via APIs.

Behavior

Once you can identify a user reliably, tracking their actions over multiple visits can help build a more accurate picture of what they’re looking for. Common scenarios include tracking what topics they read about most, which products they tend to purchase (or browse and reject), whether they prefer to visit in the morning or late at night, and so on. As with most of the building blocks of personalization, it’s important to remember that this data is a limited view of what’s happening: it tracks what they do, not necessarily what they want or need. Content Strategist, Karen McGrane sometimes tells the story of a bank whose analytics suggested that no one used their the site’s “Find an ATM” tool. Further investigation revealed that the feature was broken; users had learned to ignore it, even though they wanted the information.

Consumer Databases

Some information is impossible to determine from easily available signals — which leads us to the sketchy side of the personalization tracks. Your current visitor’s salary, their political views, whether they’re trying to have a child, and whether they’re looking for a new job are all (thankfully) tough to figure out from simple signals. Third-party marketing agencies and advertising networks, though, are often willing to sell access to their databases of consumer information. By using tools like browser fingerprinting, these services can locate your visitors in their databases, allowing your users to be targeted for extremely tailored messages.

The downside, of course, is that it’s easy to slide into practices that unsettle your audience rather than engaging them. Increasingly, privacy-conscious users resent the “unearned intimacy” of personalization that’s obviously based on information they didn’t choose to give you. Europe’s GPDR, a comprehensive set of personal data-protection regulations in effect since May 2018, can also make these aggressive targeting strategies legally dangerous. When in doubt, stick to data you can gather yourself and consult your lawyer. Maybe an ethicist, too.

2. Segments: Conclusions You Draw Based on Your Information

Individually, few of the individual signals we’ve talked about so far are useful enough to build a personalization strategy around. Collectively, though, all of them can be overwhelming: building targeted content for every combination of them would require millions of variations for each piece of content. Segmenting is the process of identifying particular audiences for your tailored content, and determining which signals you’ll use to identify them.

It’s easy to assume the segments you divide your audience into will correspond to user personas or demographic groups, but different approaches are often more useful for content personalization. Knowing that someone is a frequent flyer in their early 30s, for example, might be less useful for crafting targeted messages than knowing that they’re currently traveling.

On several recent projects, we’ve seen success in tailoring custom content for scenarios and tasks rather than audience demographics or broad user personas. Looking at users through lenses like “Friend of a customer,” “browsing for ideas” or “comparison-shopper” may require a different set of signals, but the usefulness of the resulting segments can be much higher.

Radical Truth

It’s hard to overstate the importance of honesty at this point: specifically, honesty with yourself about the real-world reliability of your signal data and the validity of the assumptions you’re drawing from it. Taking a visitor’s location into account when they search for a restaurant is great, but it only works if they explicitly allow your site to access their location. Refusing to deal with spotty signal data gracefully often results in badly personalized content that’s even less helpful than the “generic” alternative. Similarly, treating visitors as “travelers” if they use a mobile web browser is a bad assumption drawn from good data, and the results can be just as counterproductive.

3. Reactions: Actions You Take Based on Your Conclusions

In isolation, this aspect of the personalization puzzle seems like a no-brainer. Everyone has ideas about what they’d love to change on their site to make it appeal to specific audiences better, or make it perform more effectively in certain stress cases. It’s exciting stuff — and often overwhelming. Without ruthless prioritization and carefully phased roll-outs, it’s easy to triple or quadruple the amount of content that an already-overworked editorial team must produce. If your existing content and marketing assets aren’t built from consistent and well-structured content, time-consuming “content retrofits” are often necessary as well.

Incentivization

The ever-popular coupon code is a staple of e-Commerce sites, but offering your audience incentives based on signal and segmenting data can cover a much broader range of tactics. Giving product discounts based on time from last purchase and giving frequent visitors early access to new content can help increase long-term business, for example. Creating core content for a broad audience, then inserting special deals and tailored calls to action, can also be easier than building custom content for each scenario.

Recommendation

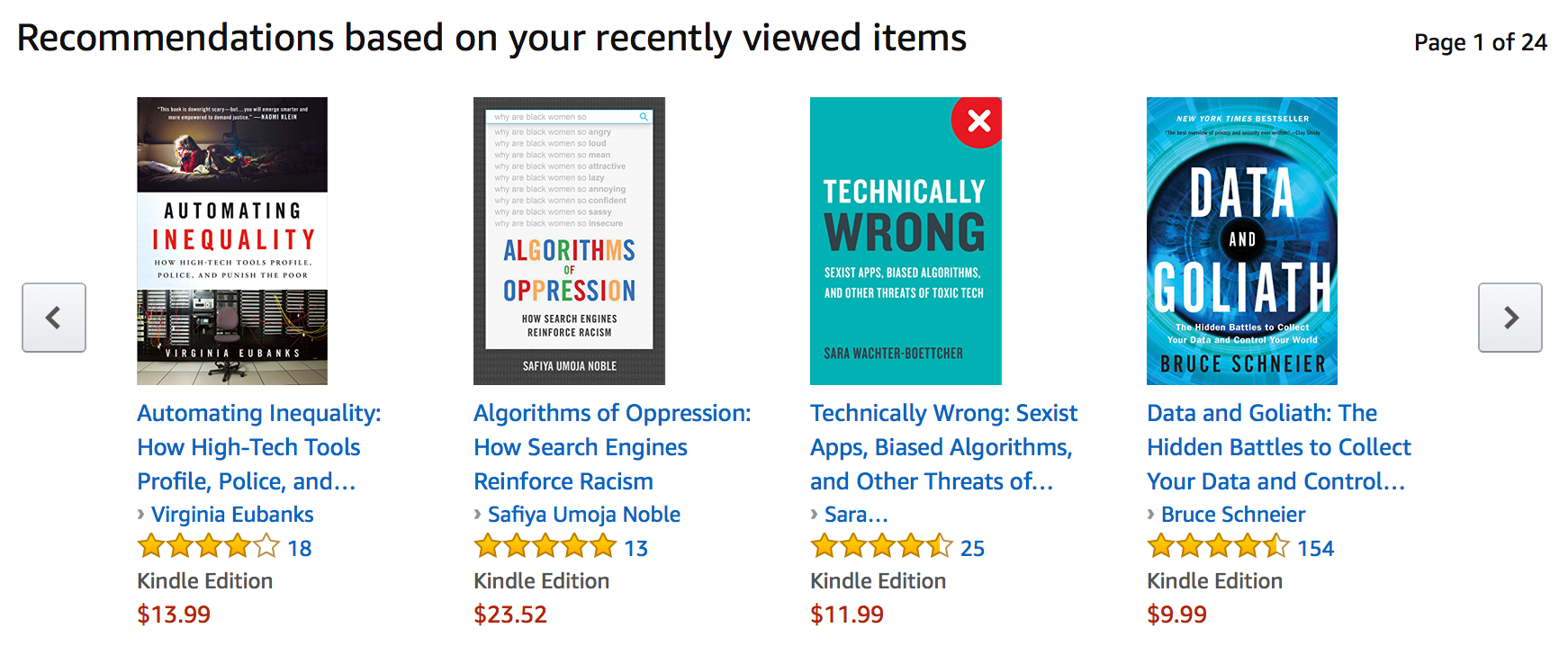

Very little of the content on your site is meant to be a user’s final destination. Whether you’re steering them towards the purchase of a subscription service, trying to keep them reading and scrolling through an ad-supported site, or presenting a mall’s worth of products on a shopping site, lists of “additional content” are a ubiquitous part of the web. Often, these lists are generated dynamically by a CMS or web publishing tool — and taking user behavior and signals into account can dramatically increase their effectiveness.

The larger the pool of content and the more metadata that’s used to categorize it, the better these automated recommendation systems perform. Amazon uses detailed analytics data to measure which products customers tend to purchase after viewing a category — and offers visitors quick links to those popular buys. Netflix hired taxonomists to tag their shows and movies based on director, genre, and even more obscure criteria. The intersections of those tags are the basis of their successful micro-genres, like “Suspenseful vacation movies” or “First films by award-winning directors.”

Prioritization

One of the biggest dangers of personalization is making bad assumptions about what a user wants, and making it more difficult in the name of “tailoring” their experience. One way to sidestep the problem is offering every visitor the same information but prioritizing and emphasizing different products, messages, and services. When you’re confident in the value of your target audience segments, but you’re uncertain about the quality of the signal data you’re using to match them with a visitor, this approach can reduce some of the risks.

Dynamic Assembly

Hand-building custom content for each personalization scenario is rarely practical. Even with aggressively prioritized audience segments, it’s easy to discover that key pages might require dozens or even hundreds of variations. Breaking up your content into smaller components and assembling it on the fly won’t reduce the final number of permutations you’re publishing, but it does make it possible to assemble them out of smaller, reusable components like calls to action, product data, and targeted recommendations. One of our earliest (and most ambitious) personalization projects used this approach to generate web-based company handbooks customized for hundreds of thousands of individual employees. It assembled insurance information, travel reimbursement instructions, localized text, and more based on each employee’s Intranet profile, effectively building them a personalized HR portal.

That level of componentized content, however, often comes with its own challenges. Few CMS’s out-of-the-box editorial tools are well-suited to managing and assembling tiny snippets rather than long articles and posts. Also, dynamic content assembly demands a carefully designed and enforced style guide to ensure that all the pieces match up once they’re put together.

4. Metrics: Things You Measure to Judge the Reactions’ Effectiveness

The final piece of the puzzle is something that’s easy to do, but hard to do well: measuring the effectiveness of your personalization strategy in the real world. Many tools — from a free Google Analytics account to Adobe Sharepoint — are happy to show you graphs and charts, and careful planning can connect your signals and segments to those tools, as well. Machine learning algorithms are increasingly given control of A/B testing the effectiveness of different personalization reactions, and deciding which ones should be used for which segments in the future. What they can’t tell you (yet) is whether what you’re measuring matters.

It’s useful to remember Goodhart’s Law, coined by a British economist designing tools to weigh the nation’s economic health. “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Increased sales, reduced support call volume, happier customers, and more qualified leads for your sales team may be hard to measure on the Google Analytics dashboard, but finding ways to measure data that’s closer to those measures of value than the traditional “bounce rate” and “time on page” numbers will get you much closer. Even more importantly, don’t be afraid to change what you’re measuring if it becomes clear that “success” by the analytics numbers isn’t helping the bottom line.

Putting It All Together

There’s quite a bit to chew on there, and we’ve only scratched the surface. To reiterate, every successful personalization project needs a clear picture of the signals you’ll use to identify your audience, the segments you’ll group them into for special treatment, the specific approaches you’ll use to tailor the content, and the metrics you’ll use to judge its effectiveness. Regardless of which tool you buy, license, or build from scratch, keeping those four pillars in mind will help you navigate the sales pitches and plan for an effective implementation.