Just had a wonderful and wide-ranging conversation with @ivanstegic for an upcoming episode of his podcast. Along the way we had a chance to talk about the influence @HyperCard on a certain way of conceptualizing “software” and “information” and how it interacts.

Quite a few folks have written insightful pieces on Hypercard’s connections to the early web. One of its most valuable qualities was the “scalability” of its complexity.

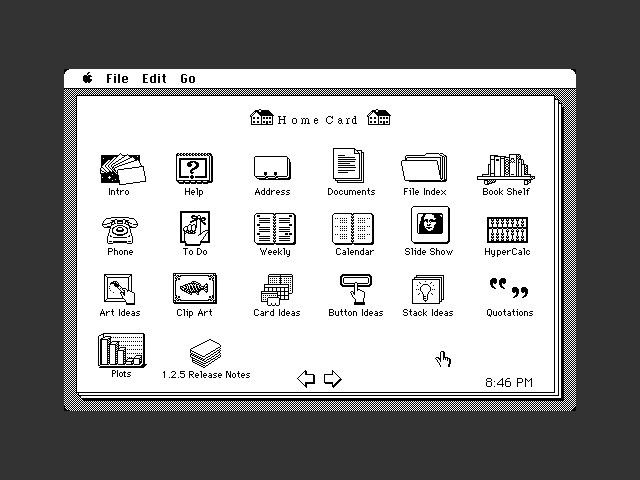

Hypercard documents were organized as “stacks” of “cards” — its earliest prototype was literally a black and white paint program with clickable “hot spots” that linked multiple paintings to each other. At its simplest, a kid could turn it into a high tech flipbook.

Complexity came in layers, quite literally. The “cards” that made up the “stack” also shared a “background” — like animation cells drawn on vellum, then placed over a shared backdrop. Changing the background changed all the cards.

Then, the elements beyond painted pixels arrived: “Fields” could be placed on a card (or in the background) to hold editable text. “Buttons” served as clickable links to other cards (or even other stacks of cards).

Stringing together those primitives — and applying sufficient elbow grease — made it possible to build stuff similar to static web sites. Address books, choose-your-own-adventure stories, and so on.

But underneath simple behaviors like “Click to change cards” was a surprisingly sophisticated foundation: a programming language called “HyperTalk” responding to the “click” event. Revealing that code — and changing it! — could run calculations, play music, display images…

And behind that “click” was a real event model; Fields, too, could be clicked. Buttons received “mouseOver” and “mouseOut” events… and you could intercept and respond to them, too. You could even write HyperTalk scripts that sent those events to other objects…

But none of that was apparent at first glance, not to a curious 9-year old kneeling on a dining room chair to click around on a borrowed Mac Plus. You could start just by painting. Drawing a silly face with the mouse. And being curious.

The slow, steady revealing of HyperCard’s capabilities was exciting and empowering, like unlocking a new room in a familiar house. More importantly, the new revelations were consistent with the old ones — they didn’t break or invalidate what you knew… just built on it.