One of the things that’s always intrigued me about digital projects — and these days, content strategy is a kind of digital project — is that I really, honestly believe that very few people are DOING A BAD JOB. There’s a lot of broken stuff, but for the most part our community has TONS of really smart and talented people in good teams doing great work.

The problem is that it is really, really hard to keep a good thing running smoothly when circumstances change, or an organization grows, or the people who created the good thing leave for a new job and someone else step in to run it.

Since you’re here, you’re probably familiar with the idea of Strategy and Tactics working together.

The way we usually put it, strategy is your gameplan for achieving specific business goals, and tactics are the actions you take to carry out a strategy. Good tactical execution goes in circles without a sound strategy guiding it, and a brilliant strategy falls apart without solid tactical follow-through.

Even with those two pieces in place, though, even when smart, skilled people nail down a solid strategy and execute it… it still feels like the WAY those smart people made their decisions about the project gets washed away with time, and the lessons have to be relearned over and over.

Maybe that’s just skill, or experience, you know? Maybe it’s an ineffable, irreproducible quality. But it’s always bugged me, and I’m always looking for interesting perspectives on “why.”

It turns out there’s actually huge body of thinking and writing about this. One theory — a theory I like a lot — is that there is this third piece called “doctrine” that describes your beliefs about how things work — the constraints your strategy has to work within, the strengths and weaknesses of the tools at your disposal, the ways that your different teams support each other, and how your competitors pursue their goals. The idea is that unless everyone is on the same page with that doctrine, things inevitably run aground as soon as priorities shift or different people have to make judgement calls about how to solve new problems.

The good news is that if your team isn’t completely in flames, you’re probably thinking about this stuff already. In most organizations, it’s not done as deliberately as strategy or tactics, but we can fix that.

The bad news is that the reason there’s a huge body of thinking and writing about this subject is that the “Strategy, Tactics, Doctrine” breakdown is an integral part of military theory, and at 10am the morning after the conference party nobody wants to hear what Hugo von Clauswitz wrote about the importance of artillery.

I understand. And it’s okay, because instead of talking about military history we’re going to talk about a mystery.

Many years ago, around the time AOL was announcing a new set-top box for web browsing, I starting a new job with a nonprofit in the Chicago area. They did a lot of training events and sold lots of training materials via mail-order.

Things moved fast in those days, and while they weren’t paying attention, their web site’s “buy training materials and download it online” feature had turned into a bustling ecommerce business. They were moving about half a million a year in MP3s and PDFs, and they hadn’t even meant to. The problem was that it was so hard to find stuff on the site, fully half of our sales required live assistance from our 800 call center. It was… suboptimal.

I was hired as “web employee number one,” or the webmaster as we called it in those days, and I was supposed to to make finding and buying their digital training materials less confusing. I was very excited.

My first task was diving in to find out what kind of data we had about each one. Detailed descriptions? Excerpts? Date of publication? No, none of that stuff. But what we did have was a “Vegetarian flag.”

After days of digging into our wonky, home-made CMS, I discovered that we didn’t have any way to store the name of a speaker who’d delivered a talk, but every PDF file, MP3 file, and grainy little quicktime movie had been faithfully marked as “NOT VEGETARIAN.”

No one who’d built the web site was still there, so it took a couple of weeks asking around. Eventually one of the nonprofit’s volunteers who happened to have gone to choir with the original webmaster clued me in.

She explained that they’d never anticipated selling downloadable files at all; it was built to sell conference registrations. But those conference registrations came with a free lunch, so they’d give you a printable PDF of a ticket you could turn in at lunch time. Thus, the ‘vegetarian’ flag.

As time went on, they added downloadable versions of the actual conference materials. Then they made it possible to buy the materials even if you hadn’t attended. Then they started splitting up the sessions and the training materials so you could buy them ala carte! But under the hood, the web site was humming along happily, selling meal tickets until I arrived to “improve the product information.”

Now, we went on to rebuild the whole thing from scratch and make a our own different and innovative mistakes, but I learned a lot from the adventure. For years I thought it was an example of “not thinking ahead,” but over time I realized there’s no way to predict EVERYTHING you might need in the future.

Remember that bit at the start of the talk? The problem wasn’t that anyone had done a BAD JOB on the web site. They needed an event management system, they built an event management system, and it kept working even as more and more requirements were bolted onto it.

Over the years I’ve come to realize that Vegetarian MP3 stories are pretty common. Sometimes it’s product information in the CMS, sometimes it’s the company newsletter, sometimes it’s how the customer knowledge base is organized, or the style guide.

Every time, the team’s doctrine — their perspective on what tools will work well and why, about the resources the organization has to work with, about what might change in the future — goes unrecorded and things eventually break down.

Alas, this brings us back to military theory.

I have a lot of mixed feelings about this, because I think our culture is already way too eager to look at everything in life through the lens of war. George Lakoff — an American linguist — has written a lot about how the metaphors we use to explain complicated phenomenon can shape how we conceptualize other aspects of our lives. Using the language and the ideas of warfare as a guide can acclimate us to a poisonous view of existence, where everything we do is a fight to the death, and we “conquer or be conquered” are the only choices we have.

If you have EVER been in the same room as a CEO or business consultant, you’ve heard of The Art Of War. It’s the first real book about the theory of war — written around 500 BC by the Chinese general Sun Tzu — and it warped an entire generation of dudes who watched the movie Wall Street and decided, yeah! Business IS just like war!

If we really internalize that metaphoe, I’m pretty sure this makes CMS vendors arms dealers, and while I have strong feelings about Gutenberg, I do not believe it is a war crime.

That said, Sun Tzu wrote some BANGERS. To put it in perspective, he described the nuts and bolts of the “strategy versus tactics…” discussion 2500 years ago, a century before the Greeks invented actual nuts and bolts.

War is a complicated group activity that humans have been doing and studying and theorizing about for a really, really long time. Armies have to train and coordinate large groups of people with varying levels of skill and experience to accomplish goals they didn’t choose in a rapidly changing environment while other groups try to stop them. Team sports have a lot of similar characteristics, but the stakes for war are usually a lot higher.

Staggering amounts of time, money, and human ingenuity have been focused on questions of logistics, science, risk management, and operations. The US military’s research brought us Cheetos and the McDonalds McRib sandwich; with some significant moral and philosophical caveats, it’s worth studying what other insights those efforts have produced, and that’s what we’re going to try to attempt here. Let’s make Doctrine our Cheetos.

So, with that caveat, I find it really fascinating that the idea of “military doctrine” as a distinct field of study arrived in the 1700-1800s: despite our long history of talking about war in general, doctrine is a relatively new innovation that emerged during a period of VERY rapid change, when several independently important trends converged.

First, European nations had spent a couple centuries colonizing the planet and stealing the world’s curry, spices, and relics. They were flush with money and also had a keen interest in maintaining large standing armies — they could afford them, they could justify them… but training them at scale was a nightmare.

Second, changes in technology — everything from widespread use of gunpowder to the arrival of steam trains — were radically altering what kinds of tactics were viable. Effectively coordinating lots of different groups of soldiers over a distance became more important than simply massing the biggest army in one place. What constituted a “good judgement call” was changing rapidly.

Third, the ubiquity of the printing press and mass literacy meant that a new generation of soldiers was sitting down and writing giant tomes about HOW ARMIES SHOULD OPERATE. They were documenting lessons learned about what worked and what didn’t, what principles should stay consistent and what tactics should change based on context.

In short, the world was changing; money was flowing; demand exploded for a new class of trained, professional soldiers; and mass publishing made it possible for experienced practitioners to share their approaches and cross-pollinate. Over time, various nations began documenting “the way we run our army” in manuals that could be printed and given to every soldier as part of their training. The domain of “good judgement” and “hard-won lessons” transitioned from “lore and wisdom” to something systematic, something that could be taught at scale, evaluated regularly, and updated when circumstances changed. By the time the 20th century rolled around, it was possible to talk meaningfully about specific countries’ distinctive military doctrines, in part because they’d written and were using using standardized manuals to train their armies and leaders. You could literally get copies of those manuals to read, compare, and study how they changed over time.

Which brings us to an actual specific example: the US Army’s ADP 1-01. It stands for ‘Army Doctrine Primer 1” and it was last updated around 2019. It’s not universal; the US Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps also have their own “Doctrine Primers” but they share a lot foundational materials. For the rest of the talk, when I mention definitions and terminology, I’m going to lean pretty heavily on this book in particular.

I like it a lot for this purpose, because the way ADP 1-01 breaks explains the elements of Doctrine and their application is particularly clear and conveniently compatible with the way we often talk about Content Strategy and Content Tactics.Even their grim jokes are familiar. In the introduction where they define “doctrine” they note that “Whatever 51% of the team is doing” and “The opinion of the most senior person in the meeting” are two common colloquial definitions of “doctrine.”

Then, helpfully, they proceed to break it down into five key pieces.

Principles are shared perspectives that affect the decisions you make. Another way of saying it might be, they’re lenses you filter your goals through to determine what approaches are reasonable or acceptable.

Some of your principles might be assumptions about the way the world works. Others might be be beliefs about what matters and what doesn’t matter, or moral and ethical lines that you’re not willing to cross, no matter what the goal.

A good rule of thumb is that new goals shouldn’t change your principles. If they do, you’re not really describing principles, just preferences. Consistent principles are one of the key ways Doctrine provides continuity when everything else is changing.

So, according to the Army’s breakdown, the next element of Doctrine is tactics. This one actually made me scratch my head when I first read the definition, because in our community I was used to thinking of it as “strategy is planning, tactics is implementation.”

Now, to clarify, they aren’t saying that doing stuff is doctrine; technically, that’s “operations.” But the shared tactical playbook you’re all working from? That’s part of your doctrine.

The other interesting element of this description of tactics is that it’s more specific than simply “actions you take” or “work you do.” From this perspective, a “tactic” is a particular configuration of people in particular roles doing particular things to produce a particular outcome. A tactic is a set of choices about how to allocate limited resources. Without that element, it’s just tasks.

In one of the good Thor movies, there’s a scene where the characters Thor and Loki are going up and elevator and quickly discussing how they’re going to get past some guards. Thor says, “We could do ‘get help…’” Loki says, “We’re not doing ‘get help.’” And the doors open and he sighs and goes limp, and Thor shouts, “Help! Help! My brother, he’s dying!”

Using this definition, “Get help” is a tactic. It’s not the only way you could achieve a goal, and there are even lots of ways you could do “Get Help,” but it also has specific fundamental elements. You need two people, it requires you commit both of them, and it requires the element of surprise. You might come up with different variations on it that you can choose based on circumstances. But the tactic, the particular shared playbook everybody works from to understand how their individual role operates as part of the tactic to achieve the goal? That’s “get help.”

The next piece of the puzzle is techniques. They’re basically like non-prescriptive ways of doing a particular task. “Here are five good ways to do X, and their strengths and weaknesses.”

I like this way of capturing them, because as an industry it’s really easy to get invested in the idea of “Best practices” and “best in breed tools.” But the whole idea of Doctrine is that best is a trap. Awareness of strengths and weaknesses and contextual fit is where it’s at.Treating things like “Podcasts” or “sponsored content” or “AI chatbots” as techniques that can be used — if we understand their strengths and weaknesses in a given context — rather than THE FUTURE or THE BEST or THE NEXT PIVOT… that puts a lot of conversations with vendors in a different context. Stakeholders, too.

So far we’ve touched on a couple of elements that inherently rely on judgement and context. On the flip side, good doctrine also captures the stuff that CAN’T vary. “Product returns happen THIS WAY. Period. full stop.” “Legal compliance requires pages go through these steps before they’re published.”

Capturing thee things explicitly allows newcomers to understand where they do and don’t have flexibility. That leaves more bandwidth for the judgment calls and contextual decisions.

Finally, the fifth element is one that I’m guessing is familiar to everybody here: shared terminology, aka Taxonomy. I will say, one of the things that amused me deeply was that chapter four of that ADP 01-1 book is just a big ol’ taxonomy guide.

Everybody loves them a taxonomy. And it matters, because part of coordinating is making sure we’re speaking the same language, that we don’t have different ways of talking about the same thing or confusingly similar ways of describing very different things.

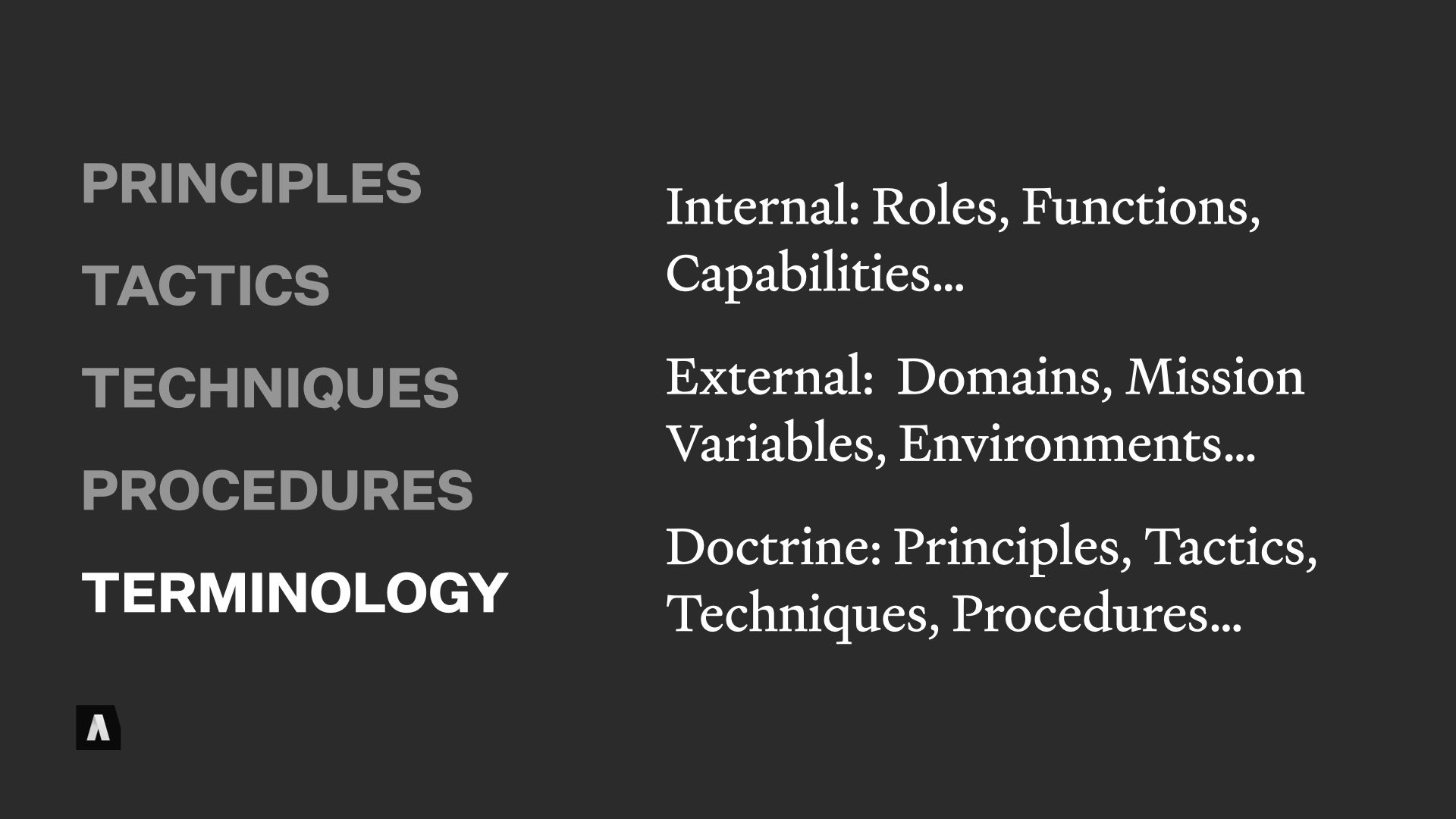

On of the things I find really fascinating — because I am a taxonomy nerd — is how the Army in particular breaks things down. They have internal-facing terms, like “what is a role” and “what is a capability”, and then they list a bunch of roles and capabilities. So when we they “we’re very good at X”, everyone knows what X means, and there’s an unambiguous definition of it that anyone who’s confused can be pointed to.

They also have external terms, or words that are used to describe the context in which they exist and work. In business this could be different categories of competitor or different market cycles. For the Army, it’s different kinds of literal terrain and climate

And then like any good taxonomy, their shared terminology guide lists the five elements of doctrine again, which technically makes the book recursive.

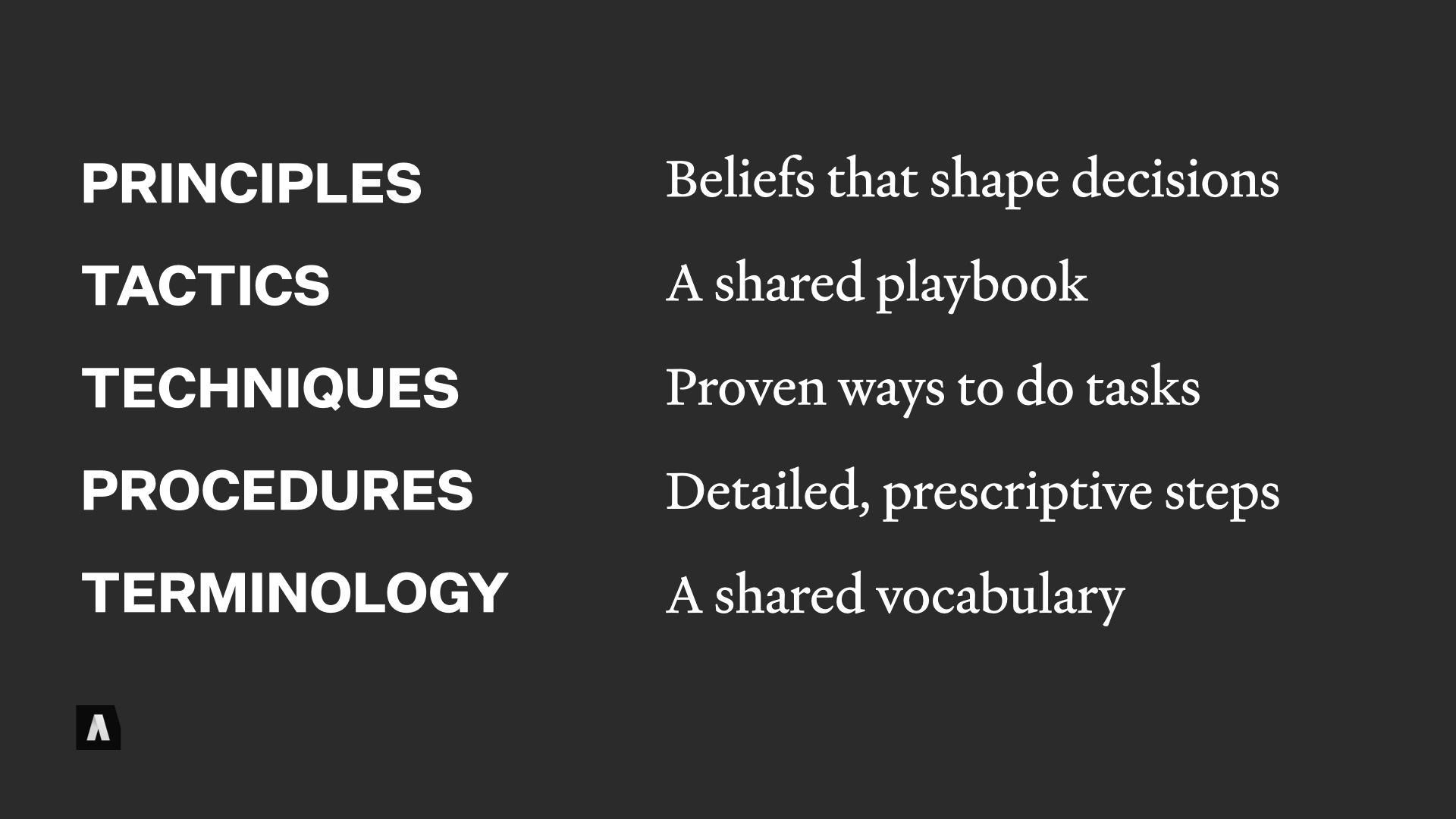

So, zooming back out, we’ve got our five elements.

Principles are beliefs that shape your decisions, tactics are your shared playbook, techniques are proven ways to do particular tasks, procedures are detailed prescriptive steps that everyone has to follow, and terminology is your shared vocabulary to make communication clearer and faster.

Some of these pieces are familiar, others (I think) have long lived in the gaps between our strategic plans and our tactical decisions. Together, they’re a pretty useful way of describing the invisible connective tissue that shapes our decisions.

A way of describing our doctrine.

Now, I know I’ve been a little cagey about a specific definition of “doctrine.” For better or worse, that goes with the territory. Every document that captures doctrine is, in and of itself, an opinionated take on what lessons and what guidelines and what ideas belong in “doctrine.”

The meta-discussion about what makes something ‘doctrine’ and not just operations or strategy or — heck, just us sitting around brainstorming about what ideas we think would be cool — is an important one. And despite the differences, there are some useful patterns that lots of military theorists seem to agree on.

In general, “doctrine” is descriptive rather than proscriptive; it describes what has been tried and tested and seen to work. There may be parts of it that are proscriptive (like procedures or taxonomy terms) but those are clearly called out, while the “playbook” parts people can choose from based on their judgement have a different role.

Second, doctrine (in the sense that we’re talking about) is institution rather than individual.

What that means is that doctrine describes what a group believes and how it does things. That’s not the same as “the opinion of each person in the group” or “what a vocal member of the group insists should be adopted” or even “what the highest ranking member of the group thinks.”

If you and I are discussing a way to do things, that’s probably useful and meaningful — but it’s not our doctrine. It’s a discussion about our doctrine.

One of the writers I came across said that doctrine is only really official when an institution adopts it and describes it and teaches it. Now, I think that articulating the “invisible and unexamined” doctrine of an organization can be very important, especially in the early phases. But my hot takes about how we should work are not institutional doctrine.

A third idea that comes up a lot — is that doctrine is based on lessons learned, not ideas we want to try.

That distinction matters, because we’ve talked about about the capturing the strengths and weaknesses of different tools, how different techniques play out in different contexts, and so on — but those aren’t just theories, they’re are lessons that have to be learned. They can be learned by your team, or by studying what’s happened in other teams, or by listening to folks who’ve been around longer and tried it themselves in the past…

But until SOMEONE actually attempts the tactics and applies the principles and uses the techniques, and you have a chance to examine the results to see how well they worked, it’s just speculation. That process of ideating and experimenting is valuable, but until it’s tried and tested it’s not doctrine.

This next idea is one that I’ve talked about before in the context of content strategy — the idea that doctrine evolves over time, and that different parts of it evolve at different speeds. The different pieces have different rates of change.

Principles, ideally, are not the fast-changing; they should stay consistent and provide continuity as the environment and the goals and the strategies shift. Some principles may change, but others may stay untouched for the entire life of an organization.

Stuff like, tactics and techniques? Those may be tweaked and updated as different tools improve, or a member of the team figures out a new way to do a particular thing, or something that used to work well breaks and has to be abandoned. Tactics and techniques change naturally as we learn.

On the other hand, procedures? While their instructions might be rigid, the procedures themselves aren’t sacred. If the steps needed to set up a new hire’s account in the CMS change, well, the procedures changes — that’s that. No hand-wringing or consensus needed.

This idea of pace layers existing in our doctrine is useful and important because it can also guide us towards the practice of re-examining different parts of our doctrine, different assumptions and lessons we take for granted, on a regular basis.

That idea of iteration and re-examination brings us to the final point: that doctrine doesn’t stand alone. It’s part of a feedback loop in which we are continually learning what works, and remembering those lessons.

It’s easy for us to think of Strategy and Tactics as a hierarchy, or even worse, a hierarchy of authority. Like, it starts with a CEO shouting orders, and that gets turned into strategy, and that filters down to tactics, where grunts in the mud do stuff.

The idea of “doctrine” as a shared perspective is a challenge to move out of that hierarchical view. The lessons that get accumulated and become doctrine don’t originate as heated boardroom arguments. They’re learned down in the mud, where the grunts are sending newsletters and writing press releases and transcribing the podcasts and answering calls in the call center.

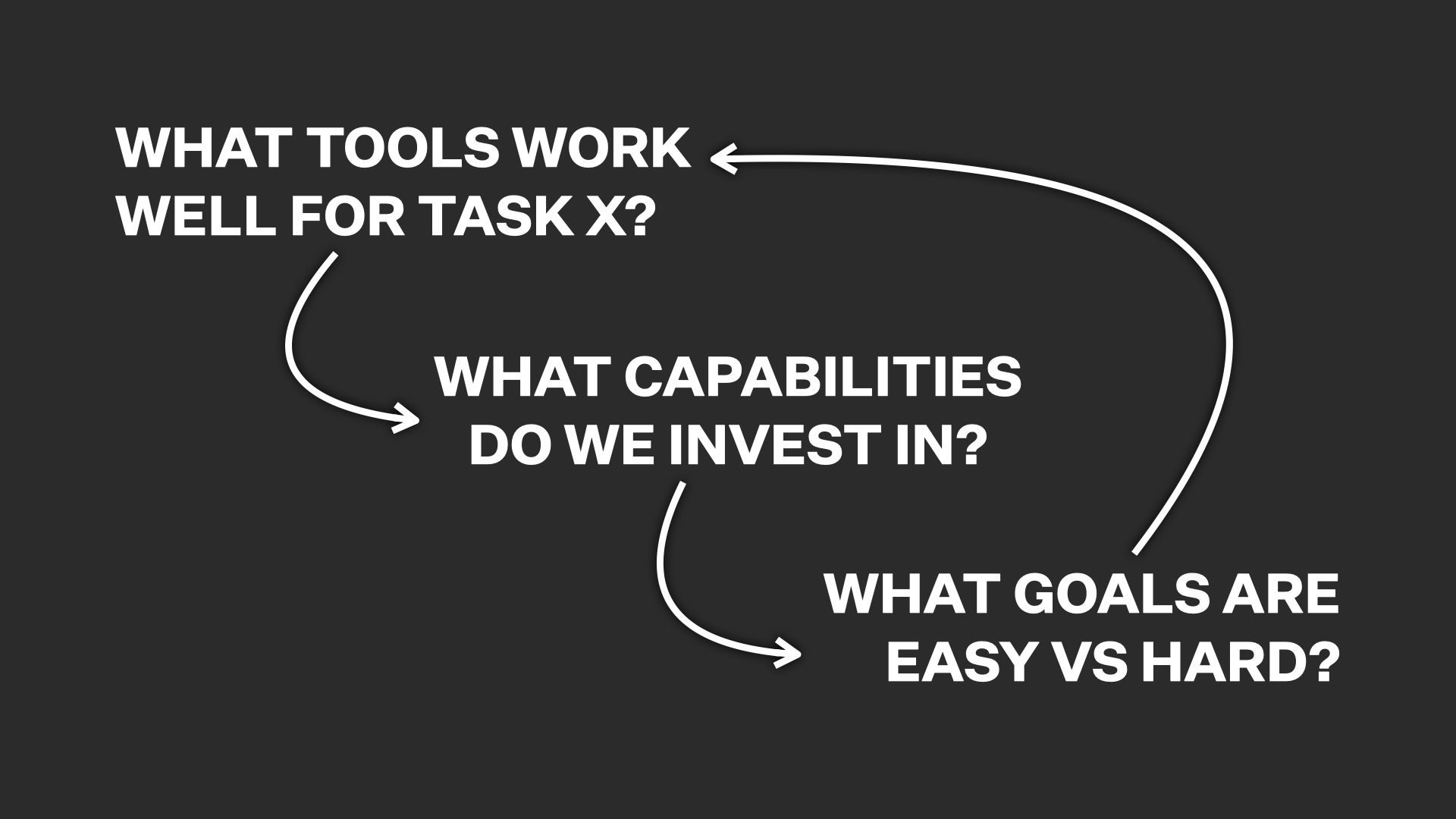

Sometimes I think of this like a feedback loop. The decisions you make about what tactics fit your available resources, what tools work well in the current environment… those decisions you make are rooted in doctrine.That, in turn, shapes what institutional capabilities you end making use of and investing in; it shapes what supporting tools end up being built; that reinforces the capabilities you invest in just like exercise builds muscle. And those shifts in institutional capability — driven by using and building the stuff you need — change what goals are easy or hard to accomplish the next time around.

The tactical lessons aren’t a dead end; they feed back into your “doctrine” of what things work and don’t work, in what contexts. Tactics shape strategic decisions, just as much as strategic goals shape tactical choices.

All right. I’ve been fire-hosing ideas for a while now, and it’s probably time to anchor them in reality.

This story is a little like historical fiction: all of the events happened, but the client is a composite of several “real” clients, anonymized to protect the innocent and the guilty alike.

My agency — Autogram — works with a lot of clients as they prepare to kick off projects like CMS migrations or multi-site redesigns or new communications initiatives. This particular organization was about to migrate to a new CMS as part of a big replatformining project. They had torn up the floorboards, and decided that while they were there, they wanted help sorting out some other complicated strategy questions.

One of the reasons I like this example is that they already had a lot of really important “doctrinal” stuff figured out, and they had a remarkable amount of continuity. Their team had been around for quite a few years, and they didn’t just understand their work: they remembered how they’d decided it was the right work to do.

We had a chance to work with them as they examined and re-assessed these things, but we didn’t have to start from scratch. It was a real treat.

First, they were able to describe some foundational ideas about where they fit with other teams and departments. The product team was responsible for documentation, support, e-commerce. Marketing owned everything brand or event related, and the comms team was responsible for corporate messaging and outreach.

We were working with the comms team on their internet site and — as is the case in our fallen world — its traditional cluster of, like, nine other websites. My theory is that no matter the size of the company there are always two jobs sites, somewhere, somehow.

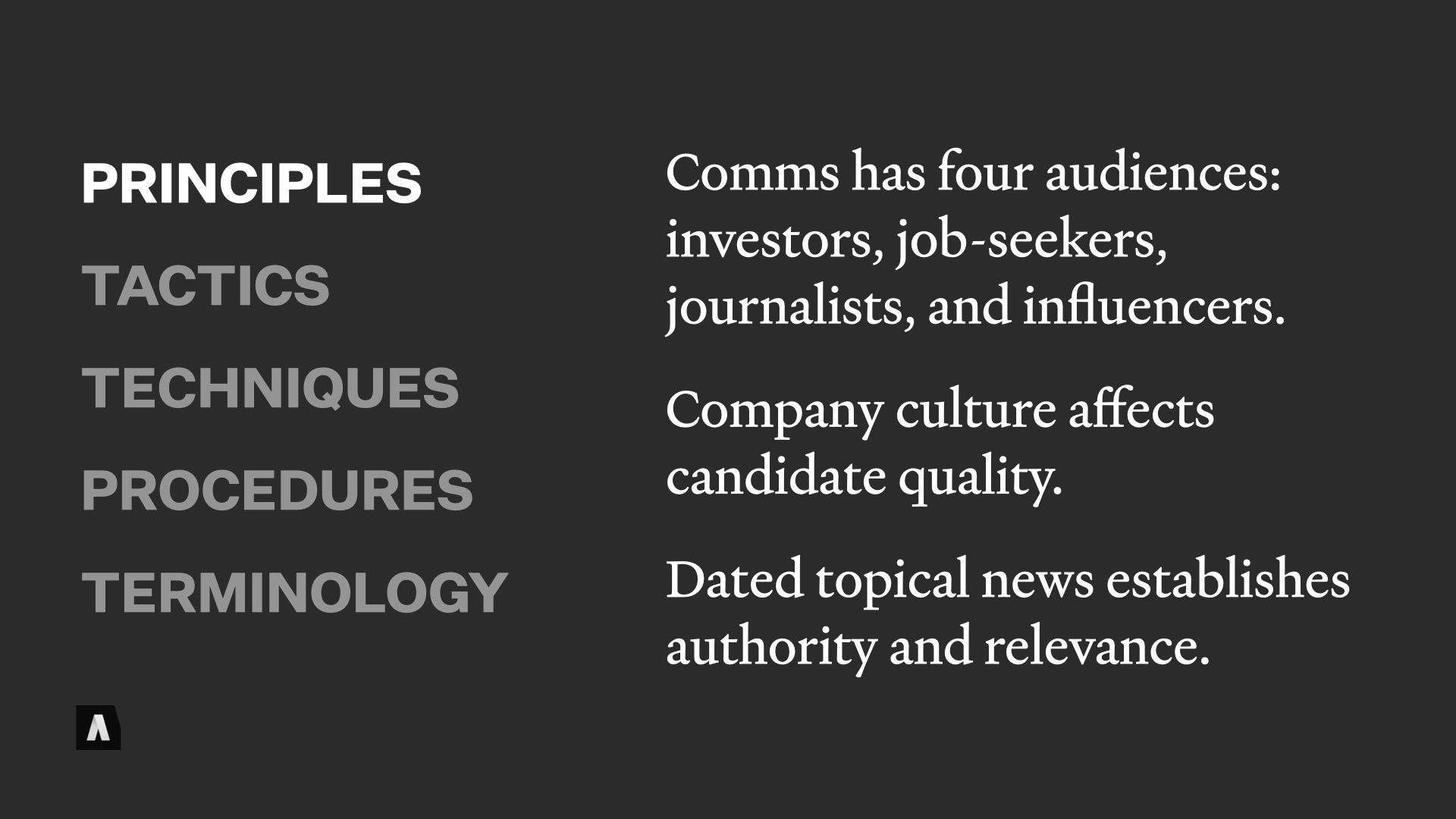

Once their place in the big picture was established, they explained some of the core principles that had shaped the kinds of content they produce.

They had four critical audiences — investors, job seekers, journalists, and influencers.They also believed that their company’s culture affected the quality of the job candidates that came in. It was important for them to talk about company culture, not just because they liked to talk about themselves, but because they believed said culture directly affected the quality of the candidates and how good of a match they were.

And they also believed that topical, timely news about the industry they were in helped them establish authority and relevance — that it reinforced the company’s position as a trend leader rather than a follower.

Now, whether you agree or not, that was a useful principle because it wasn’t a description of what they did, but a description of how they believe things work. All three of these principles are boiled down to “truth statements”. If things changed significantly and those statements no longer held true, they could look at them and say, “Hmmm, that’s not the case anymore. We need to re-assess.”

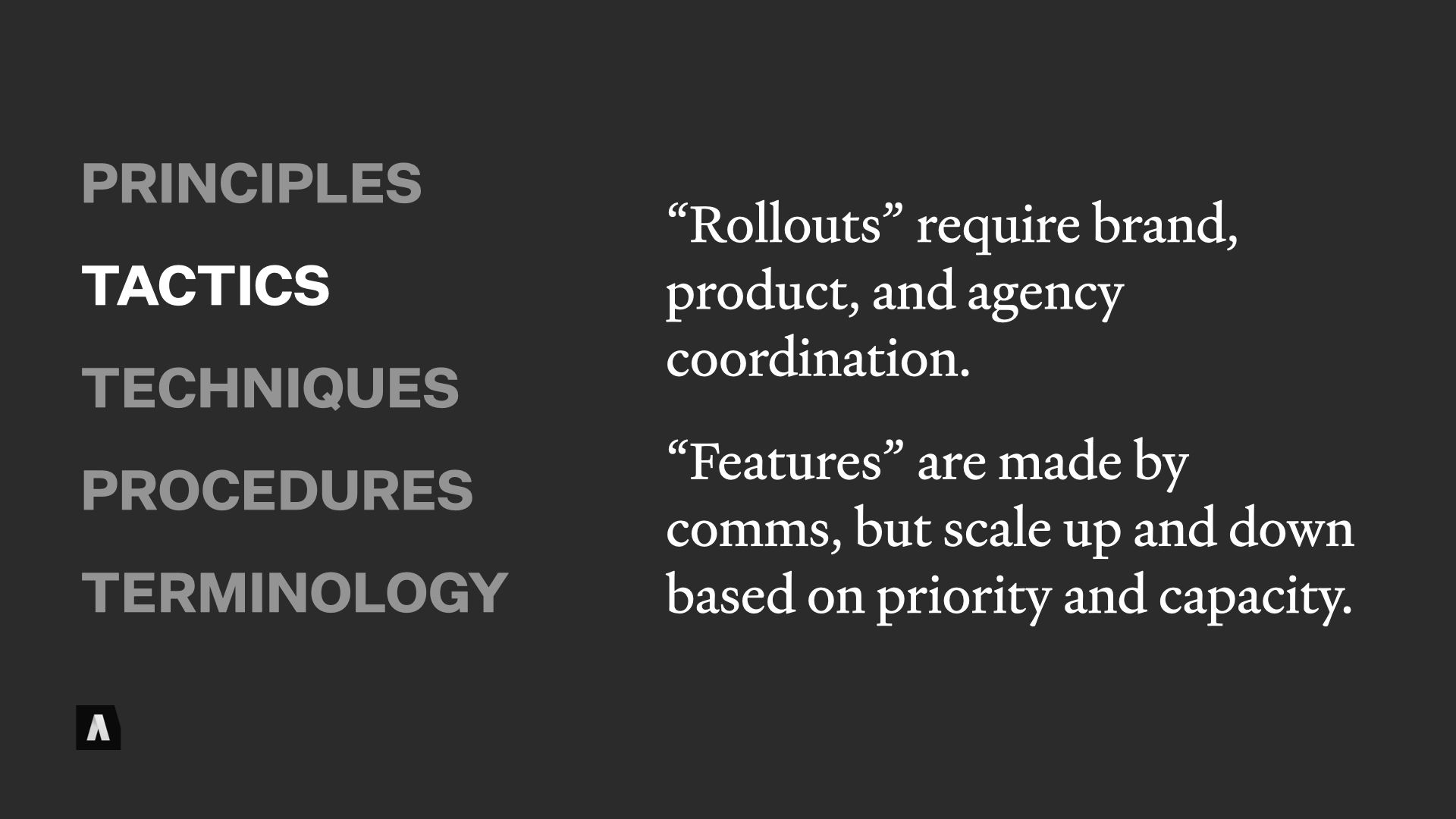

They had some well-articulated tactics, too.

“Rollouts” for example were complicated multi-element publishing tasks that required brand, product, and agency coordination. So they needed to have a playbook for what each of those teams was responsible for.

Another of their tactics was “Features.” Like, feature articles. Who’s heard of those before? I’ve seen that term in lots of different organizations. What does it mean?

Well, it doesn’t mean anything. There’s no objective definition of “feature article;” it’s a term that gets discussed and an agreed-upon shared meaning emerges inside of a particular team.

For them, features were high-profile essays and informational pages about a particular topic rather than a particular event. They were the responsibility of the comms team, and they scaled up and down based on how important the particular topic was in their strategic road map — and also based on the resources and budget they had at any given time. They had a playbook for “features,” but the resources they had to produce any given feature could vary.

Remember that idea of “techniques” as different ways of doing a particular task? This is where things started to get really interesting.

We dug into this question of features “scaling up and down” based on need and available resources. It turns out it was actually one of the significant challenges they faced with their old CMS. The range of variation across features meant one-size-fits-all CMS templates were either overkill for simple features, or too same-y for the really important ones.

So we worked with them to identify the distinct things they did to “scale up” and “scale down” features. Like, here are the five things we vary about the story structure, or the three things we can invest more time in. Maybe we’ll hire a photographer instead of using stock, or allocate an extra week or two for the writer interviewing more people and fleshing out the perspectives in the story.

Described as specific techniques, rather than just “part of the work,” those things became clearer and easier to explain to both new hires and their CMS developers. It helped them clarify what they wanted, and think about possible new was to accomplish similar goals, rather than just asking for “more flexibility.”

Their procedures were primarily things like rules for publishing investor call summaries — they have to get published in specific formats at specific times, or the government will fine us, stuff like that.

It also included stuff like, “a new editor for the CMS requires this amount of training, and IT has to do these four steps before they can log in.”

When it comes to taxonomy, I have to share one of my favorite details.

When they talked about the ways Features could be scaled up or down, they started to use the term “glamming” Like, “We’re going to glam this piece up.” I absolutely loved it, and it turned into official terminology.

And now when they talk to agency partners and one of them says, “we need this glammed up,” they can point to their glossary and say, “Ah, that means we’re gonna need at least three pull quotes, a headshot, and a gallery of product shots. Glam.”

What this gave them — this process of pulling together a clear articulation of their principles and their shared tactics and the techniques they used and so on — was a shared body of knowledge they could train with, build against, and review on the regular to be sure they still agreed about it.

It gave them a consistent way to talk about highly variable content, and to describe what they needed in their new CMS when previously they’d only been able to talk about “flexibility” in a very generic way.

It also allowed them to talk to other teams inside of the organization and higher-ups and say, here’s what we’re working with; we need a bigger budget so that we can invest in these specific tactics, which improve our results by X and Y and Z. It made a lot of things that were implicit — that had to be communicated by vibe — clearer and more explicit.

(Thank you for the one and one-half people who got the slide’s joke.)

So, if you were to tackle this inside of your organization, what are some useful first steps? Assuming that you can’t just announce your company’s doctrine, how do you approach the process?

Naturally, you start by asking questions.

Sometimes they’re big questions like, what truths about our org and our environment are currently shaping our decisions? It might be about core principles, like: Do we operate as if customer satisfaction is more important than single purchase profit?

I also like poking at the question of what doesn’t change over time. Like: “If we were to roll out a new product or pursue a new market segment, what wouldn’t we change about our messaging?” That’s usually the kind of stuff that ends up to be principle adjacent.

For tactics, one useful starting point can be the ways teams coordinate and hand off work to each other when things cross organizational boundaries. It’s a place where decisions about resources and coordination are unavoidable — we have to grapple with the question of how we divide up complex work.

Are there common patterns that we always follow across the entire organization?

Are there common approaches that exist just inside your team? Or ones that you and another team inside the org have discovered you both use? Those can be good starting points for talking about tried-and-tested tactics, named plays that you can call on instead of negotiating shared plans from scratch.

Techniques can cover a lot of ground, which makes them kind of fuzzy, but we often start by looking at the kinds of tools that are being used, and the day-to-day work processes of the folks in the trenches. And we ask them “Why?” Why do you do it this way? Were you here when that approach was chosen? Who showed you the way to do it? Have you figured out ways to make it better? Are there other ways to do it? Why would you do one rather than the other?

It’s very meat and potatoes stuff, but a lot of organizations never capture these lessons, and they lose out on important insights — improvements people have come up with, or problems that could be solved if better tools received strategic investment.

Capturing these lessons also means you can sidestep a lot of “have you tried using this tool?” fire drills. Maintaining institutional memory of the reasoning behind decisions allows you to avoid relitigating everything based on personal taste, and it also makes it easier to recognize when past decisions were based on things that have since changed.

Procedures are pretty simple on the surface; in theory a lot of organizations already have documentation and rules around anything that requires specific steps to be performed in specific ways, right? Somewhere, an engineer just said, “Sure, we have a wiki!” and an angel died.

In reality, processes that cross team or business unit boundaries are an area of particular weakness for a lot of teams. Each group of people understands their part but no one’s ever nailed down the big picture. Things like “How a product enters our product database” or “How a piece of content is flagged for and passes through legal review” can be opaque.

Teasing out the details and mapping the big picture can be incredibly valuable, even if it isn’t as thrilling as talking about principles and tactics.

I won’t spend too much time on this one, because particularly at Confab, we talk about this kind of stuff a lot. We may not have it all solved, but the importance of a shared vocabulary for communicating is… not news to many of us here.

That said, there are often places where “terminology” and “taxonomy” hide in your organization and your plans, and bringing them out into the open makes everything easier to understand. Things like “the list of industries we serve, and how we define their boundaries,” or “the market segments we use when doing personalization,” or “the way we talk about and explain the product categories we compete in” are all vocabularies that you use.

When you spend the time to figure that stuff out, clearly documenting makes the work easier to understand and apply in other areas, which makes it more valuable.

When you’re in the early phases of articulating and documenting doctrine, particularly in a big organization, the scale of it can be overwhelming. The good news is that the concept of doctrine, and the consensus that it relies on, isn’t one-size fits all; it can exist and be applied at different levels, with different kinds of focus.

I’ve been drawing on the US Army Doctrine Manual quite a bit as I explain this stuff, but it’s important to remember why that book is named ADP1-01: They have lots of other books about doctrine that apply to specific problems, or domains, or kinds of teams. In addition to “Army Doctrine” there’s tank doctrine, and firefighting doctrine. And going in the other direction, the Air Force and the Marines have their own doctrine manuals. It’s doctrine all the way down.

One of the reasons for this is simple: the playbooks and principles and procedures are different for different kinds of problems. Manufacturing and fulfillment is probably concerned with very different issues than marketing; they have different accumulated doctrine, but at a level up, the entire company has doctrine about how all of them work together.

You can start small by nailing down your project or your team’s doctrine; often, the can help other teams see what elements they share with you, and what elements are different by necessity.

Finally, that idea of teams learning from each other as they develop their internal doctrine is important. You can do that even if other teams haven’t consciously documented their doctrine in one place!

Core principles and perspectives are often trapped in places like the introduction to an editorial style guide, or in case studies about how particular client problems were solved, or in the documentation for a company design system. Sometimes it’s just aspirational fluff, but we can watch for places where a Big Idea is explained and ask, “Is this articulating a really critical perspective? What do WE think about that?”

If I were to wrap up this whole thing in one idea, it’s this: Doctrine matters, because the principles and assumptions that shape our decisions need to be preserved. So we can coordinate around them, so we can pass them on to others, and so we can quickly recognize when the world has changed around us.

I hate carving out new terms for things because there are a million of them, but I also believe that naming something makes space for it. That’s what “Content Strategy” did for a whole generation of us, and I think the need for this particular discipline is becoming just as apparent.Over time it’s become a significant part of how we help organizations find answers to their complicated problems, because without it we’re just pouring more “answers” into the pool. Those answers have a half-life, a window of time where they’re still relevant. The more we help teams articulate their doctrines, the better equipped they are to grow and self-assess in a changing world.

Thank you, and have a wonderful evening.